PRESS RELEASE

Joint exhibit with The Albuquerque Museum of Art and History features hundreds of “little jewels”

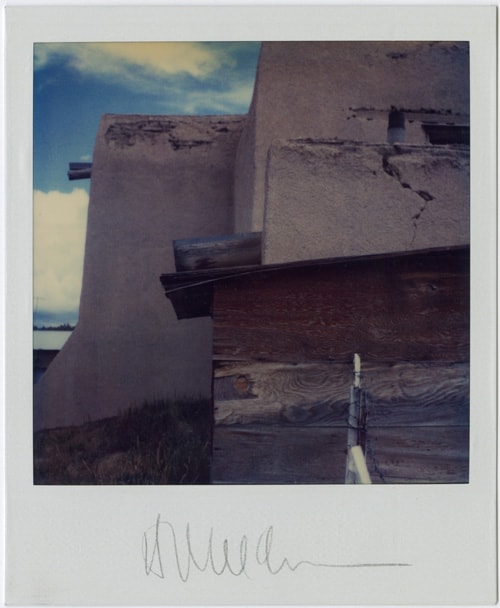

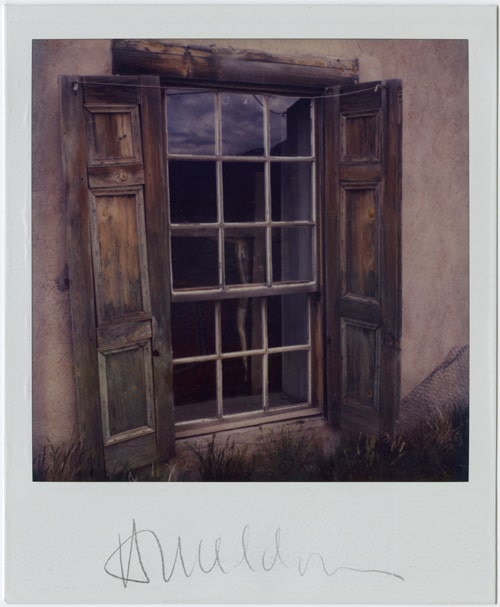

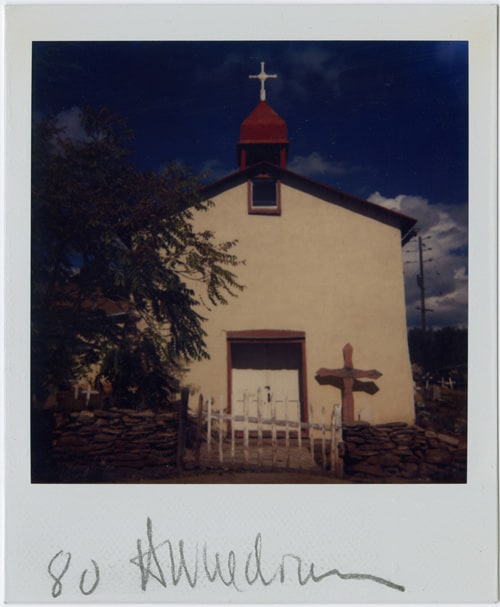

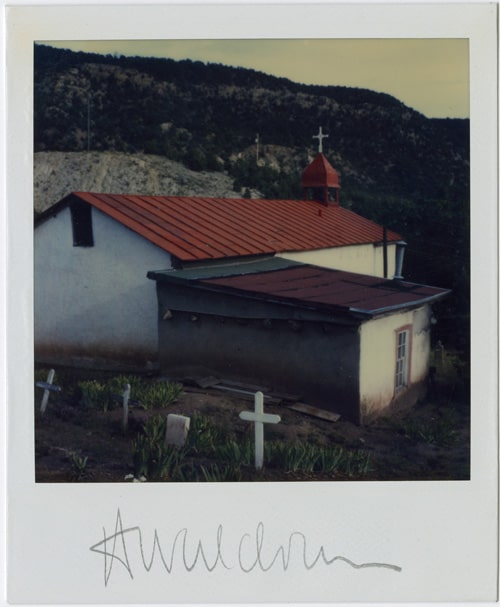

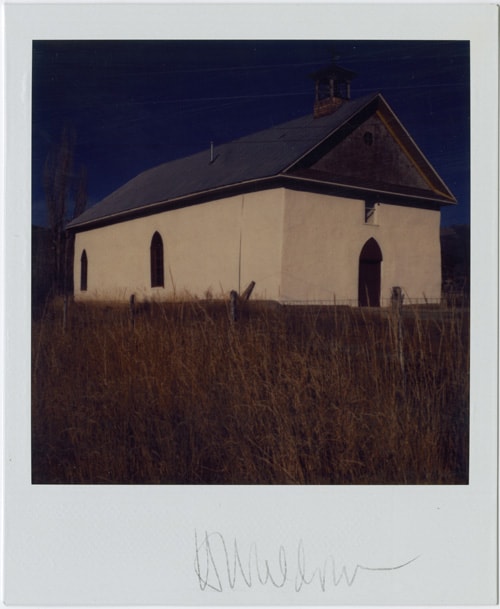

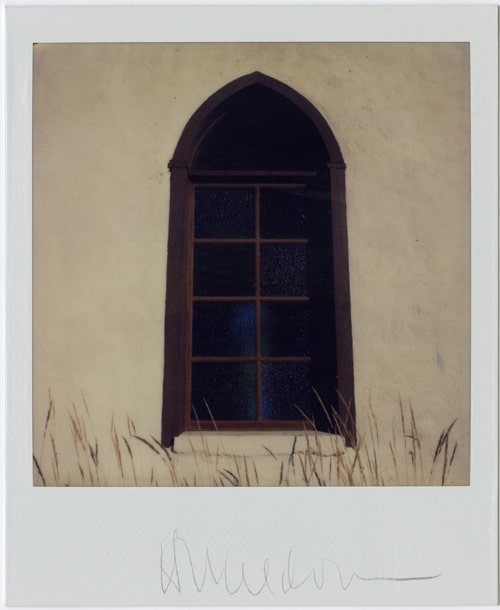

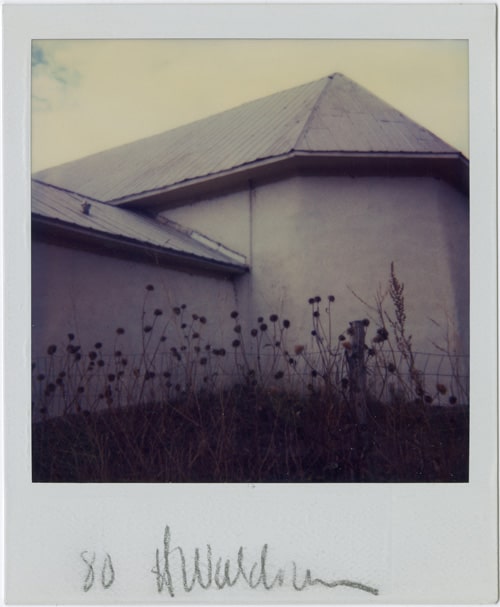

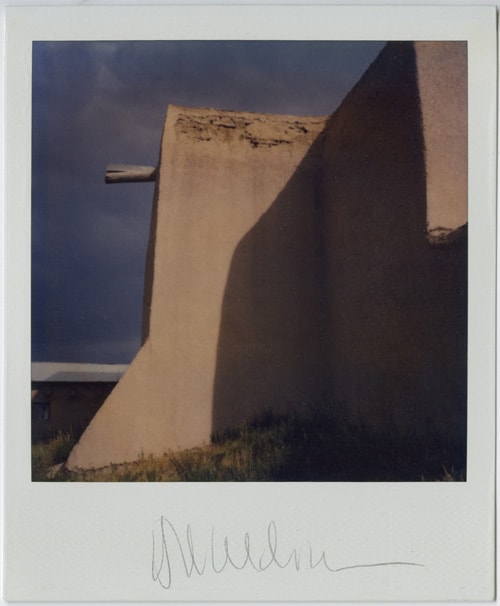

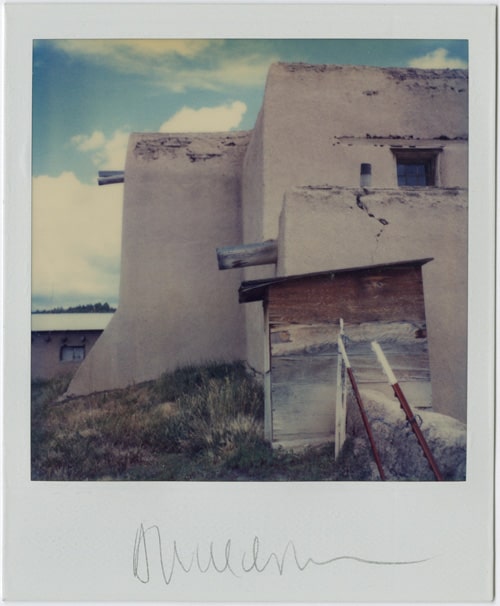

Santa Fe (Jan. 6, 2011) – A rush to catch a plane and the convenience of a Safeway grocery store led to noted New Mexico artist Harold Joe Waldrum’s long-term love affair with SX-70 Polaroid monoprints, images that Waldrum referred to as “little jewels.” The late artist’s collection of nearly 8,000 images was recently donated to the Palace of the Governors Photo Archives. A selection of them will be displayed in a joint exhibition at the New Mexico History Museum and The Albuquerque Museum of Art and History, Jan. 30-April 10.

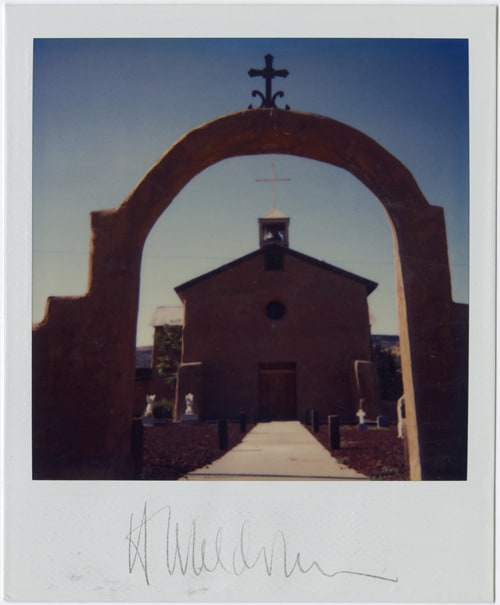

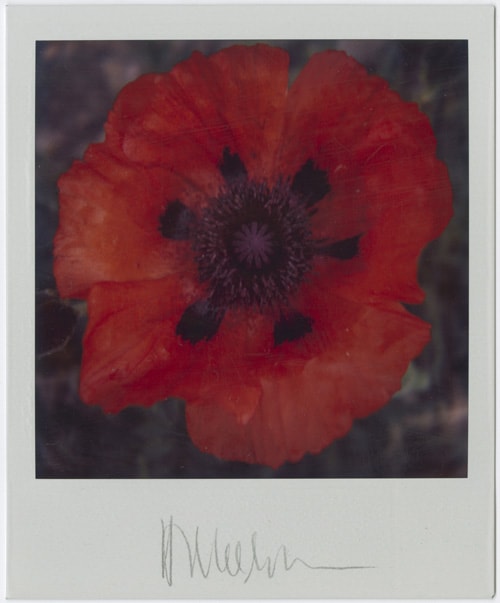

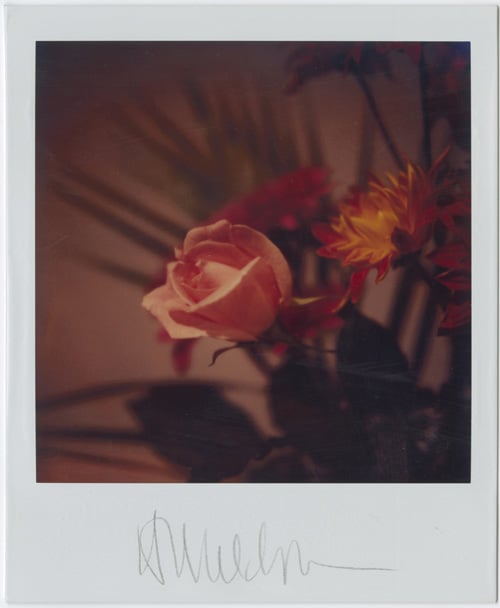

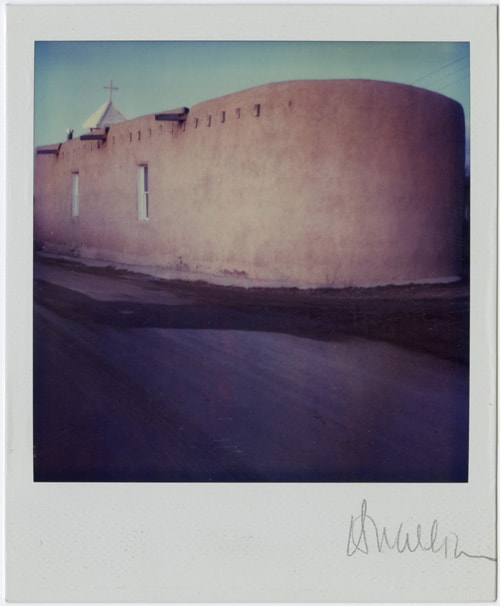

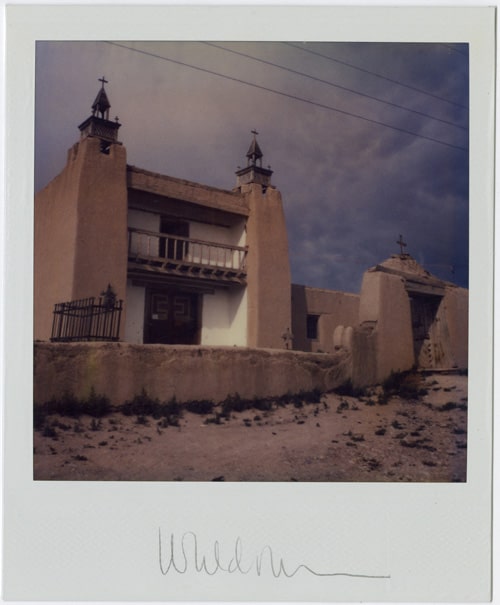

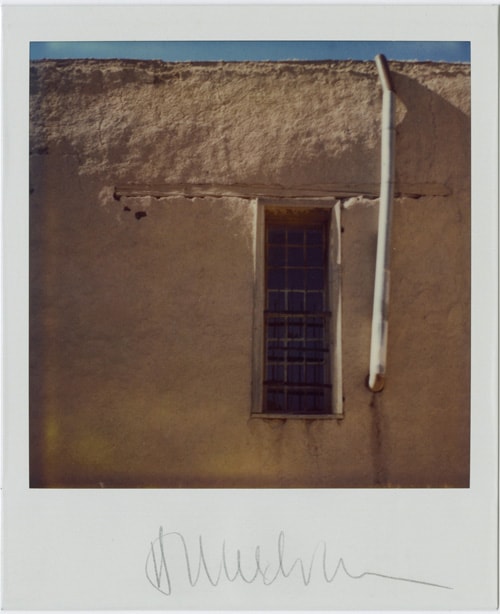

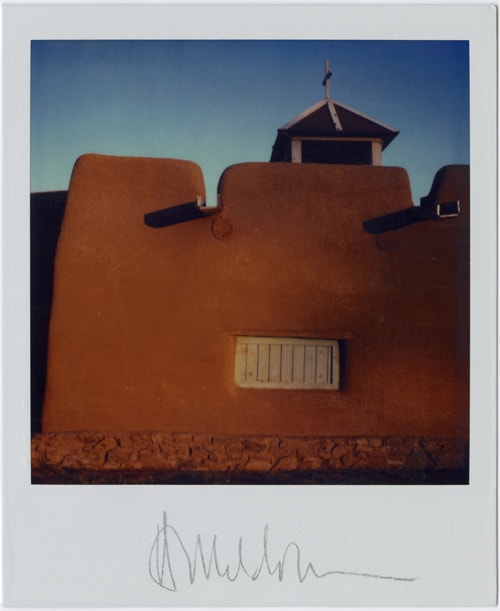

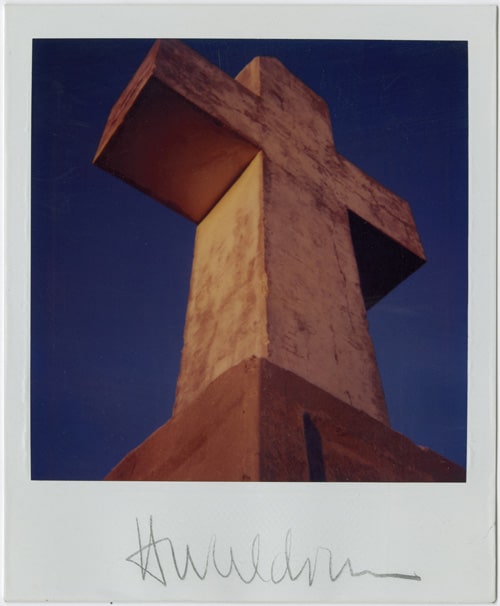

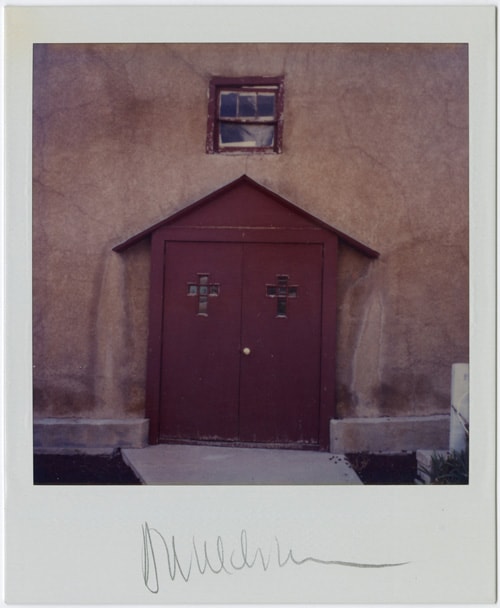

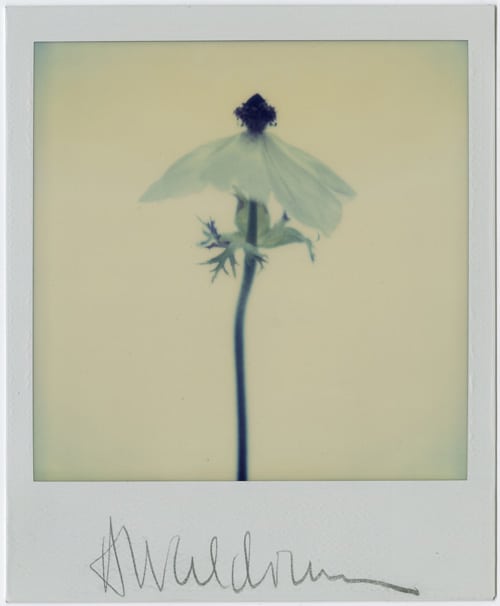

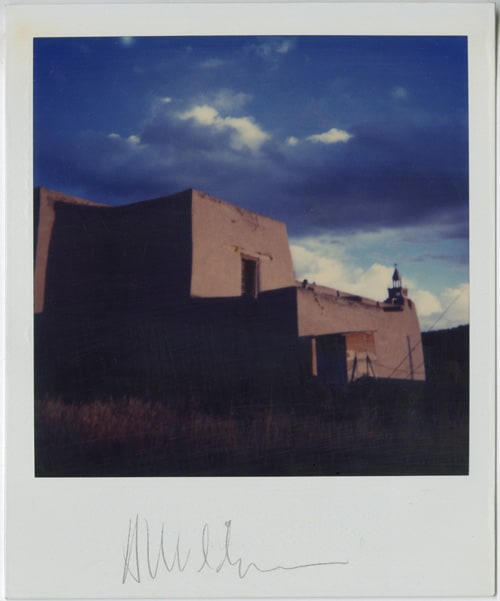

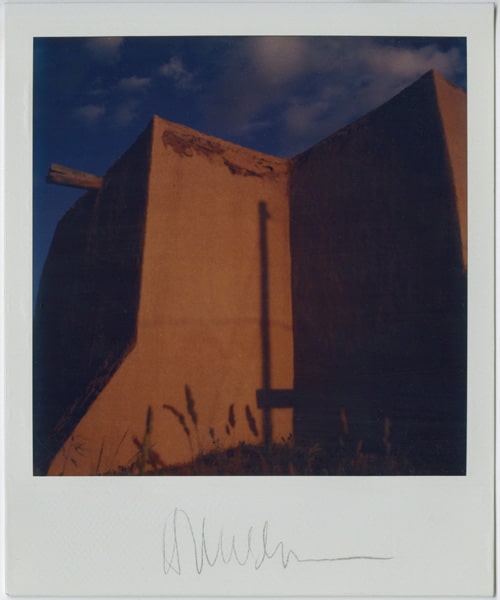

A Passionate Light: Polaroids by Harold Joe Waldrum features a total of 1,202 4½” x 3¼” images between the two museums (264 at the New Mexico History Museum; 938 at The Albuquerque Museum of Art and History). For the exhibit, Mary Anne Redding, curator of the Palace of the Governors Photo Archives, has chosen images that range from Waldrum’s studies of northern New Mexico churches to the delicate transiency of flowers.

Known primarily as a painter and print-maker, Waldrum began working with the Polaroid when he was completing his annual summer painting trip to Taos. Set to return to New York the next day, he didn’t have time to sketch San Jose de Garcia Church in Las Trampas – drawings he would need to guide him on a future painting. Lacking even a camera to take some stills, he sped to a nearby Safeway and bought a Polaroid One-Step and four boxes of film. He managed to barely beat the setting sun in exposing all the film, which developed on the car seat next to him as he drove home to finish packing.

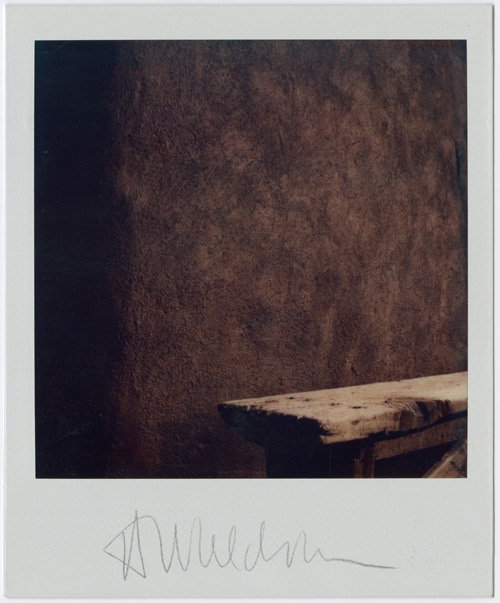

Upon returning to his New York studio, he pulled out his hurriedly snapped images and realized they captured more than shapes and colors; they documented his thinking and looking process.

From the late 1970s until his death in 2003, Waldrum faithfully carried the camera with him and captured images ranging from the spontaneously casual to the carefully composed. Nicholas Chiarella, imaging specialist for the Photo Archives, scanned the images into digital form, realizing along the way, he said, that they “deftly assert the potential …to function dually as historic documents and artistic objects.”

Born in Texas in 1934, Waldrum lived and made art in New Mexico from 1971 until his 2003 death in Truth or Consequences. His collection of SX-70 monoprints was given to the Archives by the Waldrum Estate and Rio Bravo Fine Art in Truth or Consequences. Among Polaroid aficionados, the SX-70 holds special appeal for the stability of its prints. Waldrum’s monoprints, some of them more than 40 years old, are in nearly mint condition with true colors.

The artist himself considered the images an important body of art, not mere documentation for his paintings. When anyone questioned their artistic merit, Waldrum bristled: “One gallery director said to me, `Joe, anyone can point a Polaroid camera and push a button. I will agree with him, if he will agree with me that anyone with a scalpel can cut out your appendix.”

Beyond seeing adobe churches as subject matter for his artwork, Waldrum dedicated himself to their conservation. He made videos, gave lectures, established El Valle Foundation to raise restoration funds, hosted exhibitions and spoke often about the importance of the churches not just as spiritual centers but as a means for maintaining the indigenous history and culture of Spanish New Mexico.